Stop Using the ‘Big Light’: 5 Layered Lighting Rules for a Room That Actually Feels High-End

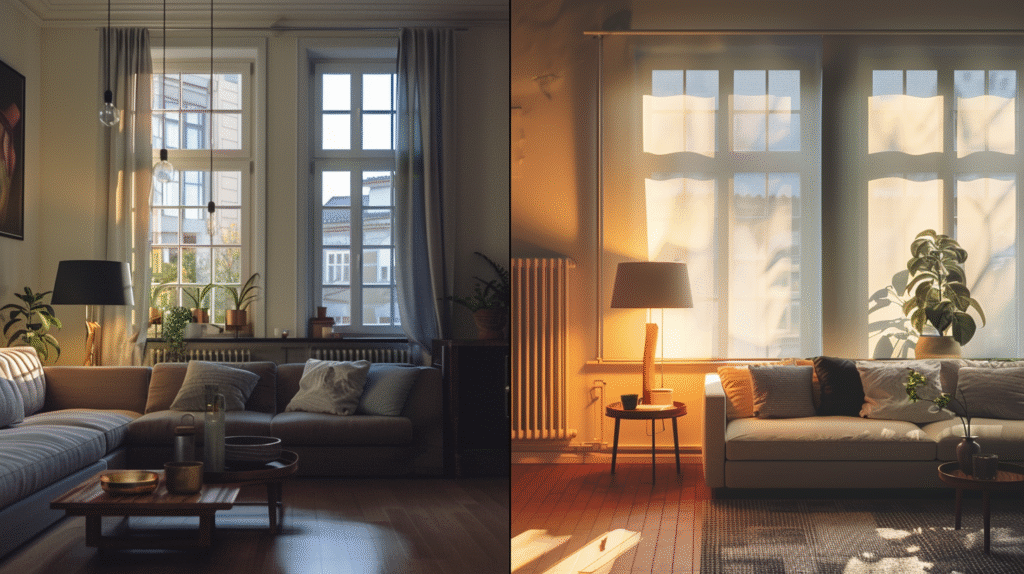

Your Room Does Not Have a Décor Problem, It Has a Lighting Problem

There is a particular kind of despair that strikes when you have done everything right. You found the sofa. You sourced the rug. You agonised for three weeks over a coffee table and another two over the colour of your walls. And then you stand in the doorway of the finished room, flip the switch—and something dies.

The culprit is the ceiling. Or rather, the single light mounted to it: that flat, relentless, unforgiving glare that flattens every texture, flushes every shadow, and turns a carefully curated room into something that feels unsettlingly close to a dentist’s waiting area. This is the Big Light. And it is the silent enemy of every room that looks good on paper but feels wrong in real life.

Interior designers have known this for decades. Hoteliers figured it out even earlier. Walk into a well-designed lobby, a Michelin-starred restaurant, or a beautifully staged apartment and you will notice—perhaps without being able to name it—that you cannot locate a single dominant light source. The room glows. It beckons. It pulls you in. That feeling has a name: layered lighting. And it is, without question, the most transformative and most underestimated tool in interior design.

Layered lighting is the practice of combining multiple light sources—at different heights, intensities, and functions—so that a room is never defined by a single point of illumination. It borrows from the logic of theatre, where mood is constructed through deliberate contrast between light and shadow. It takes its cues from hospitality design, where the goal has always been emotional comfort first and task visibility second. And it has quietly become the defining characteristic of homes that feel expensive, warm, and deeply liveable—regardless of what they actually cost.

The cultural moment has arrived for this conversation. The rise of what designers call “soft life” interiors—rooms built for comfort, sensory pleasure, and psychological ease—has made the Big Light not just unfashionable but genuinely incompatible with the kind of spaces people want to inhabit now. We have collectively stopped aspiring to the bright-and-functional and started reaching for the warm-and-considered. We want our homes to feel like retreats. Layered lighting is how they get there.

This is not about adding more lamps. It is not about installing a dimmer switch and calling it done. And it is certainly not about chasing pendant trends on Instagram and hoping the right fixture solves everything. True layered lighting is a design philosophy—a disciplined, intentional approach to how light moves through a space, what it reveals, what it conceals, and what it makes you feel.

What follows are five rules—not suggestions, not gentle guidelines, but rules—for building a layered lighting scheme that transforms a room from a well-furnished space into a genuinely atmospheric one. Each rule unpacks a principle, exposes a common mistake, and offers practical, budget-conscious, renter-friendly guidance. Because good lighting does not require rewiring. It requires intention.

Before you touch a switch or buy a single bulb, you need to understand the architecture of layered lighting. And it begins not with products or aesthetics but with function—specifically, three distinct functions that every well-lit room must perform simultaneously.

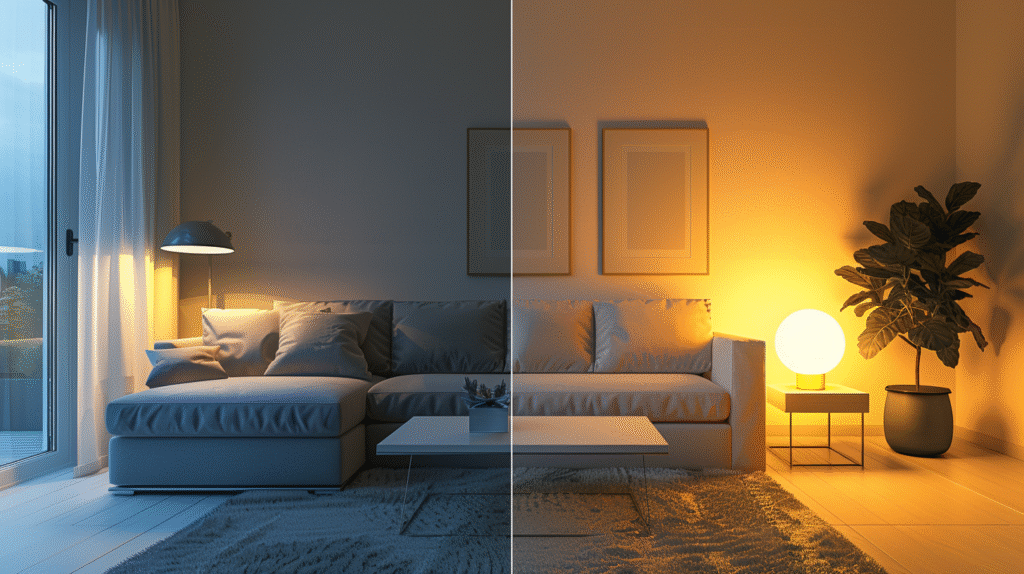

The first is ambient lighting: the general illumination that allows a room to be used safely and comfortably. This is your baseline—the light equivalent of a whisper rather than a shout. In a well-executed layered lighting scheme, ambient light is low and warm, a gentle backdrop upon which everything else is layered. It can come from a central pendant on a dimmer, uplights positioned in corners, or light bouncing off a pale ceiling from concealed sources. What it should never be is your only light source.

The second layer is task lighting: directed, functional light for specific activities. Reading, cooking, working, applying makeup—these all require light delivered precisely, close to where you need it. A table lamp beside the sofa. A desk lamp aimed at your keyboard. Under-cabinet lighting in a kitchen. Task lighting is purposeful and specific, and its presence means you never need to flood an entire room with harsh overhead light just to read a book in one corner of it.

The third layer is accent lighting: the decorative and atmospheric finishing notes that create drama, highlight architecture, and give a room its sense of depth. A picture light casting warmth over a painting. Candles clustered on a dining table. LED strips running along the underside of a shelf. Accent lighting serves no purely practical function—and that is precisely its genius. It creates the shadows and highlights that make a room feel three-dimensional rather than flatly illuminated.

Why All Three Must Be Present

Layered lighting works because human eyes evolved in a world lit by fire, sun, and shadow—not fluorescent overhead panels. We are neurologically wired to find warmth, dimension, and contrast comforting. A room with a single overhead light source contains none of these things. A room with all three layers operating simultaneously contains all of them. The subconscious response is immediate and powerful: the space feels safe, considered, and alive.

This is why you walk into a beautifully designed hotel room and exhale. You did not consciously notice that the ambient pendant was dimmed to 40 percent, that table lamps on either side of the bed were delivering warm task light at eye level, and that an LED strip behind the headboard was casting a gentle amber glow up the wall behind it. But your nervous system noticed. Every layer was doing its job. The room felt finished—not because of the furniture or the thread count of the sheets, but because the lighting was working in concert.

The Renter-Friendly Approach

The good news is that all three layers are entirely achievable without touching a ceiling or calling an electrician. Ambient can come from a central floor lamp with a wide shade aimed upward. Task is a plug-in table lamp positioned where you actually read or work. Accent is a cluster of candles on a shelf, a string of warm LED lights tucked behind a headboard, or a battery-powered picture light above the one piece of art you care about most. You are building atmosphere, not installing infrastructure.

The common mistake is treating these layers as interchangeable or cumulative rather than distinct and simultaneous. Adding more lamps does not equal layered lighting if they are all the same height, the same warmth, and performing the same function. You need separation of purpose, separation of height, and separation of intensity. Think of it like music: melody, harmony, and rhythm are not the same note played louder. They are different instruments playing different roles. Take one away and the whole composition collapses.

-

Afe Pendant Light

£296 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

ARMSTRONG FLOOR

£2,688 Add to cart -

Durham Pendant

£2,261 Add to cart

Every layered lighting conversation must begin with the most powerful light source in any room: the sun. Natural light is the foundation upon which every artificial layer should be built—and yet it is consistently treated as an afterthought, something to be managed with blackout blinds and heavy curtains rather than amplified, shaped, and then thoughtfully extended into the evening.

The first step in any layered lighting plan is to observe how natural light moves through your space over the course of a day. Where does the morning light fall? How sharp are the shadows at noon? What does the room look like at four in the afternoon in winter, when the golden hour arrives early and then disappears abruptly, leaving a cold grey emptiness? These observations tell you where your artificial layers need to work hardest and what moods they need to sustain.

North-facing rooms tend to receive cool, flat, consistent light—beautiful for art studios, less so for living rooms that need warmth in the evening. They require warmer artificial sources to prevent the space from feeling clinical after dark. South-facing rooms are flooded with warm, directional light for much of the day but can swing to stark and harsh at midday—sheer curtains or linen blinds that diffuse rather than block are your best allies here. East-facing rooms glow magnificently in the morning and fall into shadow by afternoon, which tells you exactly where to concentrate your artificial accent layer.

Reflective Surfaces as Light Amplifiers

Mirrors positioned across from windows, glossy lacquered surfaces, pale walls that bounce rather than absorb—these do extraordinary work in amplifying natural light. They do not constitute layered lighting on their own, but they create the luminous canvas upon which your artificial layers can be more lightly applied. The more natural light you can capture, shape, and sustain through the day, the less you need from artificial sources to compensate after dark.

Texture matters here too, and it matters more than most people realise. A richly textured linen wall catches light and creates depth in a way that a smooth, flat painted surface never can. A bouclé sofa, a rattan pendant shade, a rough-hewn wooden shelf—all of these interact with both natural and artificial light to create visual complexity and warmth. Dark colours, contrary to persistent myth, do not make rooms feel smaller when the layered lighting is done well. They create moody, cocooning depth that good lighting can make extraordinary. A deep forest-green wall in a room with well-considered sources does not feel cave-like. It feels like a private, sophisticated sanctuary.

Working With the Day’s Arc

The most accomplished layered lighting schemes are designed with the day’s arc in mind. Morning light is sharp, clean, and directional—artificial supplements should be minimal. Midday is often the easiest, with natural light doing most of the work. Late afternoon, particularly in winter, is when your artificial layers need to step forward gradually, extending the warmth of the day rather than replacing it with something jarring. This is when dimmer switches become indispensable, allowing you to ease artificial light upward as natural light retreats, without ever making the transition feel sudden or harsh.

The most common mistake here is installing heavy curtains to “deal with” natural light rather than managing it with intention. Natural light filtered through sheer linen is luminous, warm, and deeply flattering to both rooms and the people in them. Natural light blocked entirely creates a sealed environment that your layered lighting then has to work twice as hard to animate. Work with the sun, not against it. The sun has been setting the mood for longer than any of us have been decorating

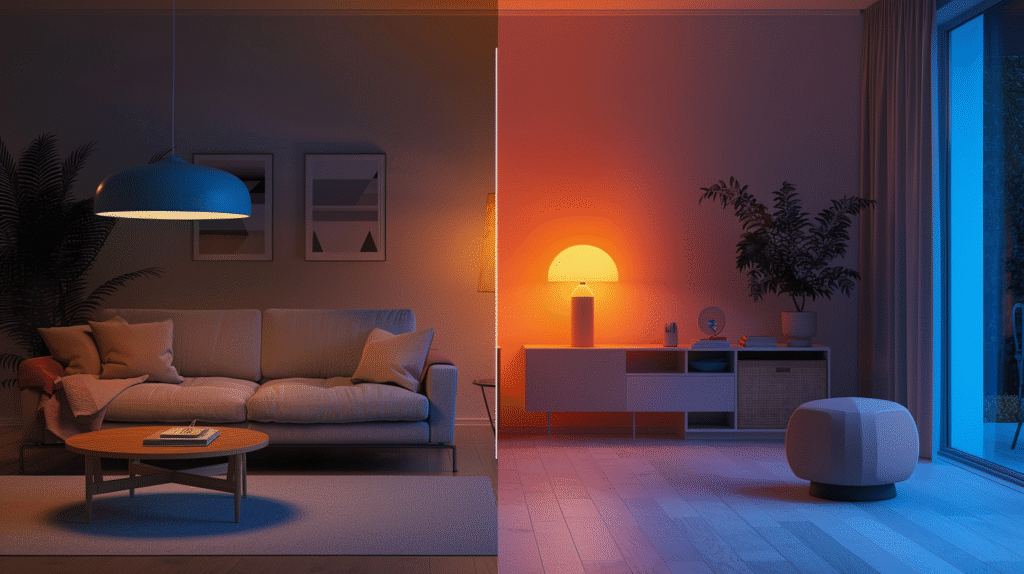

If there is one technical concept that has the single greatest impact on whether layered lighting succeeds or fails, it is colour temperature. And it is also the most commonly misunderstood—because most people buy light bulbs without thinking about it at all, and then wonder why their beautifully designed room feels cold, jaundiced, or inexplicably wrong.

Colour temperature is measured in Kelvins and describes the hue of light emitted by a source. It runs on a spectrum from warm amber at the low end to cool blue-white at the high end. For residential interiors—for rooms in which you want to feel at ease, relaxed, and at home—2700K to 3000K is the range that matters. This mimics the warmth of candlelight and traditional incandescent bulbs. It flatters skin tones, enriches the colour of wood and fabric, and creates the amber glow that our nervous systems associate with evening, safety, and rest. When you walk into a hotel room and it feels immediately welcoming, this is what you are responding to, even if you cannot name it.

Cool white light—4000K and above—has its applications. It is useful in task-specific environments like kitchens where accurate colour rendering matters, in studio spaces, or in bathrooms where you are applying makeup or checking your appearance. But deployed across a living room or bedroom, it creates a subtle psychological unease: the sensation of being in a space designed to be efficient rather than enjoyed. Fluorescent overhead strips running at 5000K or 6500K are the extreme version of this effect. They are why hospitals feel the way hospitals feel.

The Calibration Problem: Mismatched Temperatures

One of the most insidious mistakes in layered lighting—particularly in rooms where lamps and bulbs have been assembled over time from different retailers—is mismatched colour temperatures. A table lamp at 2700K sitting beside a ceiling fixture at 4000K creates a visual discord that is hard to name but impossible to unfeel. The room looks patchy, inconsistent, and vaguely unsettling. Not because any individual source is wrong, but because they are speaking different emotional languages simultaneously.

The solution is to standardise. Choose a temperature for the room and commit to it across every source. 2700K for living rooms, bedrooms, dining rooms, and hallways—anywhere you want warmth, intimacy, and psychological comfort. 3000K for kitchens where a slightly brighter quality of warm white is preferred. 4000K reserved only for under-cabinet task lighting or a home office desk lamp where colour accuracy is genuinely required.

And then there are candles, which burn at approximately 1800K—the warmest source available to us, and the one that no artificial bulb has ever truly matched. The flicker, the warmth, the almost imperceptible movement of a flame does something to a room that no LED can replicate. More on this in the accent layer, but the principle is relevant here: when you understand the Kelvin scale, you understand why candles are not merely decorative. They are the warmest, most emotionally resonant light source in your entire layered lighting scheme, and they belong in almost every room.

The Psychological Effect of Getting It Right

There is a reason that layered lighting with consistent, warm colour temperature makes people feel good in a space without knowing why. It is not abstract or theoretical—it is neurological. Warm light in the amber range signals, at a biological level, that it is evening, that the day’s work is done, that rest and connection are appropriate. Cool white light signals the opposite: alertness, activity, the office, the fluorescent corridor. When your home is lit at 4000K, your body is receiving a message that it is time to be productive. No wonder it is hard to relax.

Get the colour temperature right, keep it consistent across every layer, and you will have solved one of the most common reasons that rooms feel technically correct but emotionally wrong. It is a change you can make today, with bulbs that cost a few pounds or dollars each, and the effect will be immediate.

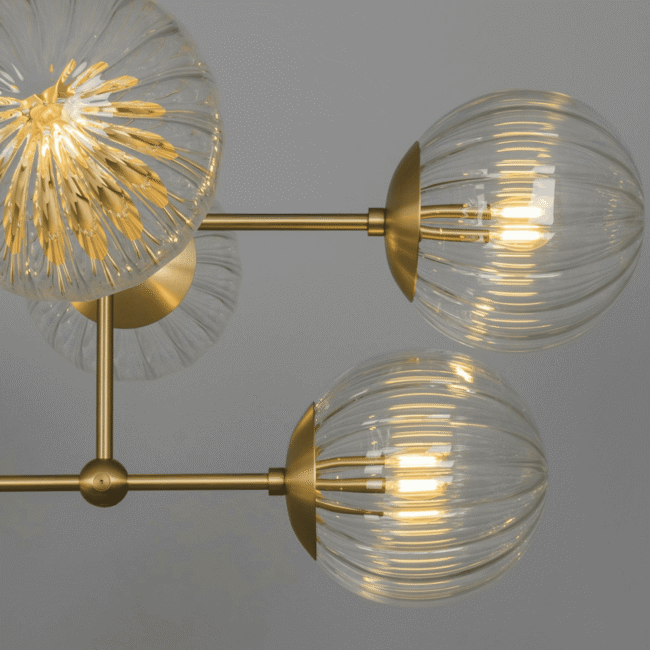

There is a paradox at the heart of how most people approach statement lighting. They spend considerable money on a beautiful pendant or chandelier, hang it in the centre of the room, and then use it as their primary—sometimes only—light source. The result is that a fixture chosen for its sculptural beauty becomes a practical workhorse, flooding the room from a single high point, and looking significantly less beautiful than it should because everything around it is flattened in uniform light.

A statement pendant is punctuation. It marks a moment—above a dining table, at the centre of a hallway, in the heart of a kitchen island. It defines a zone. It creates a focal point. But when you dim it, allow accent and task layers to step forward, and let the pendant become one voice in a conversation rather than the only speaker in the room, something remarkable happens. The fixture becomes more beautiful, not less. The room breathes. Shadows appear. Texture emerges. The eye has somewhere to move.

The Case for Dimmer Switches

If you do one thing after reading this article—just one—install a dimmer switch on every overhead light in your home. The transformation will be immediate and extraordinary. A central fixture running at full brightness is the Big Light problem stated in hardware. The same fixture, dialled to 30 or 40 percent, becomes ambient light: a warm, soft, enveloping glow that supports the layers beneath it rather than obliterating them.

Dimmer switches are available for most light fittings, including LED circuits, though you will want to check that your bulbs are specifically labelled as dimmable—not all LED bulbs are, and using a non-dimmable bulb on a dimmer circuit will cause flickering and reduce the bulb’s lifespan. Smart bulbs with app or voice control function as dimmers without any rewiring and are ideal for renters. Plug-in dimmer switches for lamp cords exist and cost very little. There are very few living situations in which achieving some degree of lighting control is not possible.

True layered lighting is not a static state. It is dynamic—responsive to the time of day, the activity underway, and the mood being sought. A room at seven in the evening when someone is reading needs a different configuration than the same room at ten o’clock when friends are over for dinner. Dimmers give you the ability to shift between these configurations without moving furniture or adding sources. They are the most underpriced, highest-return investment in interior design.

How to Use a Statement Fixture Well

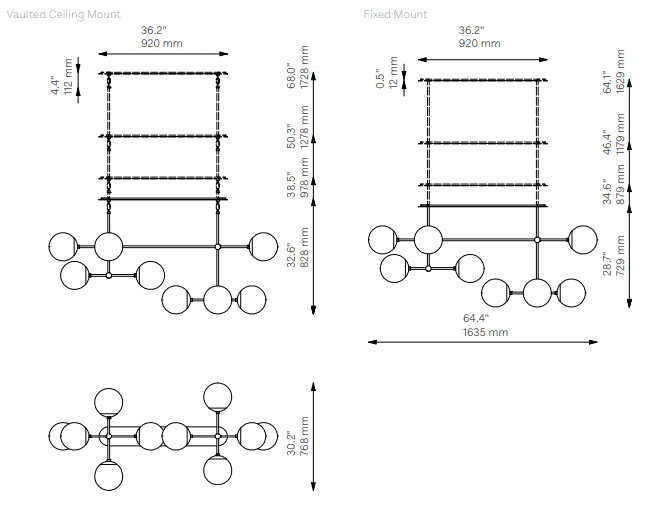

The rule is simple: a chandelier, pendant, or sculptural ceiling fixture should never be the primary source of usable light in a room. Its job is visual impact, spatial definition, and atmosphere—not illumination. Choose a shade or diffuser that creates a beautiful pool of light downward while also casting warmth toward the ceiling above. Position it to mark a zone, not to fill a room. Let task and accent layers do the practical work, so the pendant can do the atmospheric work. Consider its scale carefully: a pendant that is too small for its space disappears entirely; one that is too large becomes oppressive and crowds out everything around it.

The common mistake is buying an extraordinary fixture and then removing all other light sources from the room to “let it breathe.” This is backwards. The pendant needs other layers around it to look its best. A single, beautiful fixture in an otherwise unlit room is lonely, one-dimensional, and dramatically underpowered. Surround it with supporting layers and watch it come alive. The pendant becomes a jewel when the room around it is also luminous. Without that context, it is just a ceiling fitting in a dark space.

We arrive now at the most personal, most expressive, and most frequently neglected layer of the three. Accent lighting is where the preceding principles—ambient base, task precision, colour temperature discipline, dimmer control—find their emotional culmination. This is where a room stops looking professionally adequate and starts feeling genuinely alive.

Accent lighting exists for one purpose: to create moments. Moments of warmth, of drama, of intimacy, of delight. It is the light that catches the edge of a ceramic vase on a high shelf. The glow that emanates from behind a stack of books arranged on a deep alcove. The six white taper candles on a sideboard that make dinner feel like an occasion even on a Tuesday. Accent lighting does not illuminate the room. It illuminates the room’s character. And in doing so, it reveals the character of the person who lives there.

Candles: The Irreplaceable Layer

Candles remain unmatched. No LED technology—and the industry has tried heroically, producing flicker-flame bulbs and scented candle simulators of increasingly impressive sophistication—truly replicates the quality of candlelight. The flicker. The warmth at 1800K. The almost imperceptible breath of a flame responding to air currents in the room. The scent, if the candle is a scented one, which layers an olfactory dimension onto the visual atmosphere and makes the whole experience of being in the room richer and more complete.

If there is one non-negotiable accent layer, it is candles. They are available at every price point. They require no installation. They work in every space, from a tiny studio flat to a grand drawing room. And they do something that no fixture can: they make people feel good about being in a room, in a way that is immediate, instinctive, and universal. Keep a generous supply and use them without restraint.

Picture Lights, LED Strips, and the Art of Placement

Picture lights and art lights are among the most underutilised tools in residential design. A small, warm picture light mounted above a painting or a mirror does extraordinary things: it creates a focal point, adds warmth to a wall, and makes the room feel curated and gallery-worthy. They are available as plug-in or battery-powered options for renters, making them one of the most accessible high-impact additions in the layered lighting toolkit.

LED strip lighting, used with restraint and installed with intention, can be genuinely transformative. Running a warm LED strip along the underside of a floating shelf, behind a headboard, or beneath a kitchen island creates a halo of light that lifts a room off its surfaces and gives it depth. The phrase “with restraint” is doing essential work in that sentence. LED strips deployed as a primary source, in cool white, visible directly to the eye, are among the quickest routes to a space that looks like a gaming setup. Used sparingly, at 2700K, tucked out of direct sightline so you see the glow but not the source, they are exceptional.

Floor Lamps, Wall Sconces, and the Mid-Height Gap

Two sources deserve specific attention because they solve a problem that is epidemic in domestic spaces: the vertical mid-range, the gap between floor and ceiling where light rarely lives. Most rooms have sources at ceiling height and at surface height. The space in between—where eye contact happens, where the warmth of a room is felt when you are standing in it—is frequently dark.

Floor lamps, particularly arc designs or those with upward-facing shades, fill this gap beautifully. They cast light both upward toward the ceiling and outward across the room, creating that all-important pool of warm ambient glow at standing height. A single well-positioned floor lamp in the corner of a living room can entirely change the character of the space. It is not hyperbole: try it.

Wall sconces—whether hardwired or, increasingly, available as plug-in or battery-powered options—are equally transformative. They add light at mid-height, they create architecture on otherwise flat walls, and they are one of the signature moves of hotel and hospitality design that has filtered most effectively into residential spaces. A pair of sconces flanking a bed, a headboard, a fireplace, or a mirror does not merely illuminate. It frames. It elevates. It declares that the space was designed rather than assembled by accident.

The most common mistake with accent lighting is treating it as a luxury to be added “later” rather than a foundational layer to be planned from the beginning. In any layered lighting scheme, the accent layer is what guests notice, what creates the emotional atmosphere you are working toward, and what makes the room feel finished rather than almost finished. Plan it from day one, even if you deploy it gradually over time.

-

Abril Twist Table Lamp

£493 Add to cart -

Annie Flush Mount

£616 Add to cart -

Armstrong Linear Chandelier Light

£5,235 – £6,544Price range: £5,235 through £6,544 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

There is a scene in every well-designed home, in every thoughtfully considered hotel room, in every restaurant you have ever loved—a moment when you settle into a space and feel, without knowing why, that everything is right. The room is warm. It holds you. Something about being in it feels like a gift. You are not analysing the sofa or cataloguing the paint colour. You are simply, deeply at ease.

That feeling has almost nothing to do with furniture and everything to do with light.

Layered lighting is the invisible infrastructure of beautiful rooms. It is the discipline that separates spaces that look good in photographs from spaces that feel extraordinary in person. It is the reason that a modestly furnished room with a thoughtful layered lighting scheme can feel more expensive, more welcoming, and more alive than a lavishly furnished room lit by a single overhead source. The money is in the furniture. The magic is in the light.

The five rules laid out here are not complicated. They do not require renovation, rewiring, or a significant budget. They require attention, intention, and the willingness to switch the Big Light off and start building from the ground up—layer by considered layer.

Begin with your three layers: ambient, task, accent. Understand how natural light sets the room’s character and let your artificial sources extend it. Choose your colour temperature—2700K, warm, consistent—and commit to it without compromise across every source in the room. Put your statement fixtures on dimmers and allow them to perform their real purpose: drama, not function. And then invest care and creativity in the accent layer, where candles and picture lights and the soft glow of a lamp at the right height turn a well-lit room into a room worth living in.

Layered lighting, at its most accomplished expression, becomes the decor. Not the lamps—the light itself. The warmth that pools on a worn wooden table. The shadow that falls, just so, across a textured wall. The moment a room shifts, as evening comes, from beautiful to breathtaking. This is what layered lighting achieves when it is done with confidence, with knowledge, and with the deep conviction that the way a space feels matters at least as much as the way it looks.

Switch off the Big Light. Begin.

- Tags: Uncategorized

What do you think?

Blog

Get fresh home inspiration and helpful tips from our interior designers